Having discussed the authoritative version of the text and the stellar identifications, Grasshoff now turns towards reviewing and checking the work of previous authors, starting with Vogt. Continue reading “Scholarly History of Commentary on Ptolemy’s Star Catalog: Grasshoff (1990) – Reviewing Vogt”

Scholarly History of Commentary on Ptolemy’s Star Catalog: Newton (1977)

In the past few posts, we’ve demonstrated a rapidly forming consensus that Ptolemy’s star catalog was largely an original work. However, there were some holdouts. In

As a forewarning, this book raised a great deal of popular media attention as the alleged scheming of scientists is always a popular topic, but scientists reviewing the book have generally panned it as using flawed methodology, as we’ll see. Continue reading “Scholarly History of Commentary on Ptolemy’s Star Catalog: Newton (1977)”

Scholarly History of Commentary on Ptolemy’s Star Catalog: Gundel, Pannekoek, and Peter & Schmidt (1936-1968)

In the last post, we explored the 1925 paper by Vogt that attempted to reverse engineer entries from the presumed Hipparchan star catalog. Assuming that the coordinates derived were actually representative of such, Vogt demonstrated that Ptolemy was unlikely to have based his catalog on that of Hipparchus.

Continuing in the theme of defending Ptolemy, we’ll explore three more texts which come to Ptolemy’s defense: a book by Gundel (1936), a paper by Pannekoek (1955) and a paper by Petersen & Schmidt (1968). Continue reading “Scholarly History of Commentary on Ptolemy’s Star Catalog: Gundel, Pannekoek, and Peter & Schmidt (1936-1968)”

Scholarly History of Commentary on Ptolemy’s Star Catalog: Vogt – 1925

In our last post we had established that it was impossible for Ptolemy to have stolen all of his data from Hipparchus as indirect evidence of the number of stars that would have been included in Hipparchus’ catalog indicate that Ptolemy’s catalog had around

Thus, while it’s not necessary that Ptolemy took all of his data from Hipparchus, the possibility remains that he took some. But to determine that, we’d need more information about Hipparchus’ presumed catalog which is what we’ll explore in this post looking at an important 1925 paper by Vogt. Continue reading “Scholarly History of Commentary on Ptolemy’s Star Catalog: Vogt – 1925”

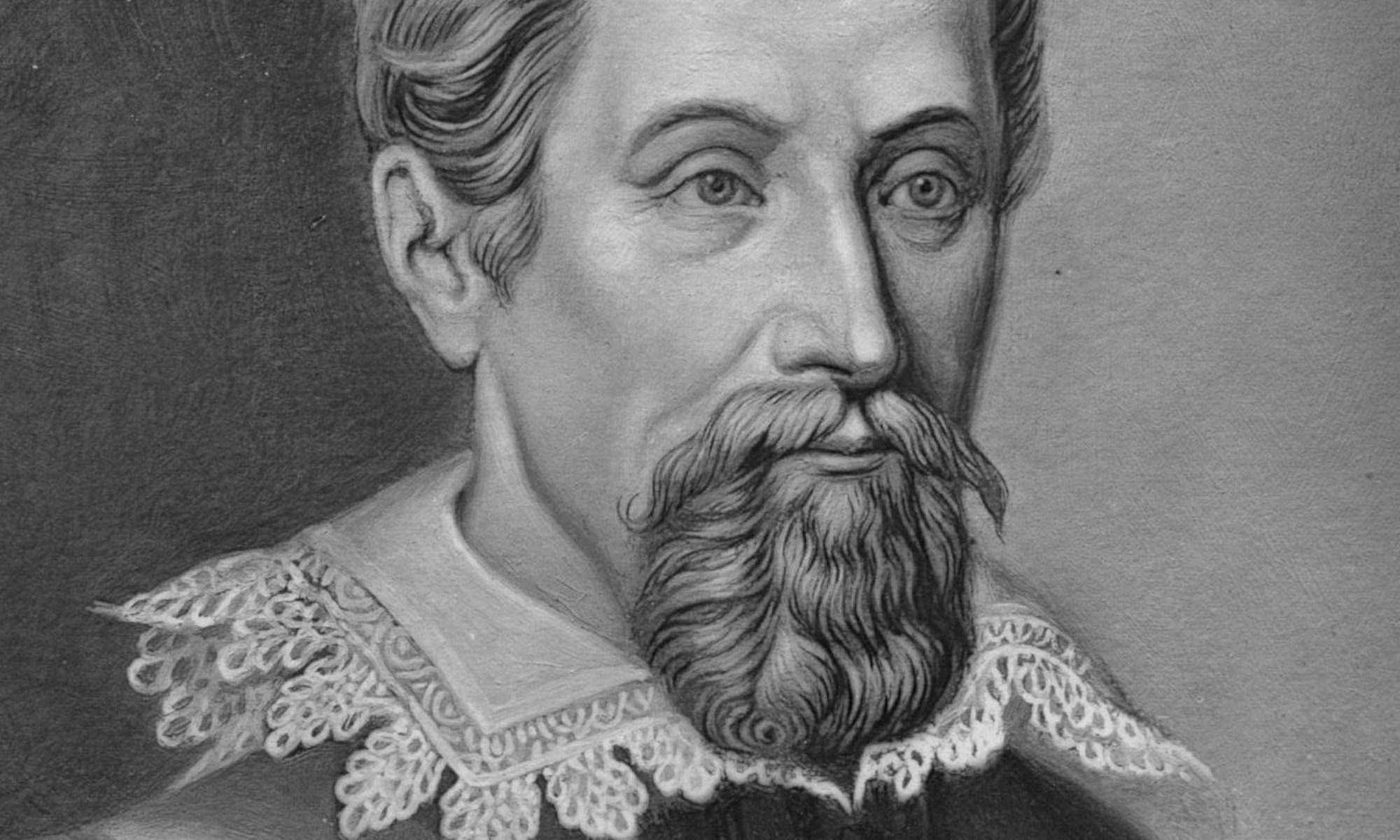

Scholarly History of Ptolemy’s Star Catalog Index

The discussion surrounding Ptolemy’s star catalog is a fascinating one. While astronomers for hundreds of years took Ptolemy’s catalog as authoritative, Tycho Brahe noticed that the positions of the stars had a

Astronomers have been debating this ever since.

Continue reading “Scholarly History of Ptolemy’s Star Catalog Index”

Almagest Book V: Scale of the Lunar Model

Now that we’ve worked out the distance to the moon at the time of the observation, we can put this information back into our lunar model diagram to work out the true scale. We’ll begin with a drawing of our lunar model at the time depicted:

Continue reading “Almagest Book V: Scale of the Lunar Model”

Continue reading “Almagest Book V: Scale of the Lunar Model”

Almagest Book V: Lunar Parallax

Chapter 11 of Book 5 is one of those rare chapters that’s blessedly free of any actual math. Instead, Ptolemy gives an overview of the problem of lunar parallax, stating that it will need to be considered because “the earth does not bear the ratio of a point to the distance of the moon’s sphere.” In other words, the ratio of the diameter of the earth to the distance of the moon isn’t zero.

However, this does pose an interesting question. We’ve previously given the radius of the eccentre as