I’m going to take a bit of a break from direct progress on the Almagest as we get to the star catalog. This is because there is, what I feel to be a fascinating and important discussion surrounding its legitimacy and I want to explore the history of this discussion, even though almost all of it is outside the range of the SCA period1. Namely, the discussion is whether or not Ptolemy’s star catalog is legitimate, one which he took the measurements himself, or if Ptolemy stole the data from an astronomer that came before him and tried to update it, but failed due to an incorrect value for the rate of precession.

This story starts when astronomers following Ptolemy got the smart idea to try to check the accuracy of his stellar positions. To do so requires two things: A very good understanding of the positions of the stars on the celestial sphere in the present, and a very good understanding of the precession of the equinoxes2.

The Islamic astronomers that studied the Almagest missed out on being able to critically analyze this because they took Ptolemy’s measurements as authoritative and used them as a basis to determine their precession similar to how Ptolemy used Hipparchus’ measurements and then divided the motion by the intervening time period. This led the Islamic astronomers to come up with a notably higher constant of precession as compared to Ptolemy. For example, in the $11^{th}$ century, al-Biruni calculated a rate of precession of $1º$ per $66$ years3. In the $13^{th}$ century, al-Tusi calculated a value of $1º$ per $70$ years. Closing in on the correct value but not quite right.

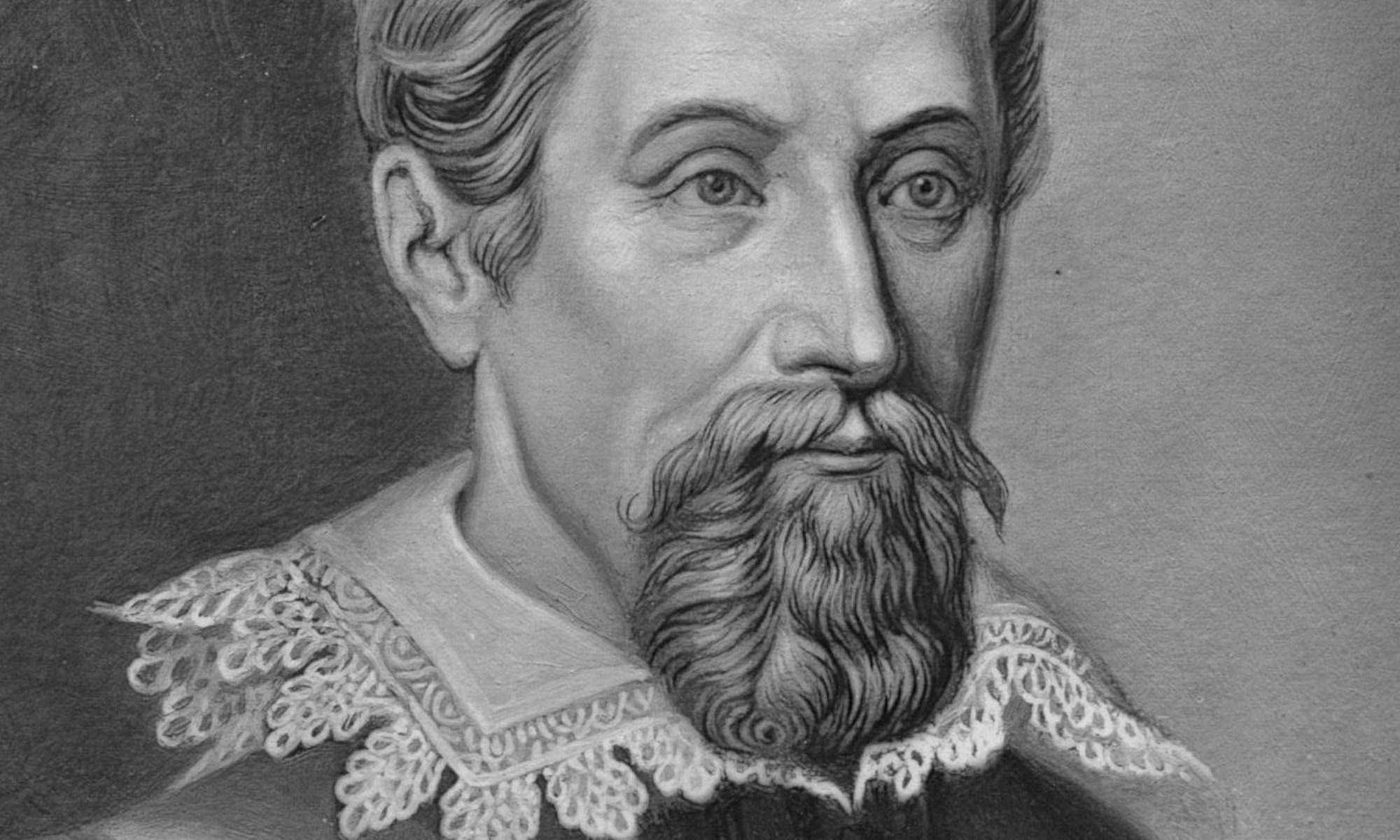

It wasn’t until the $16^{th}$ century and Tycho Brahe that both requirements fell into place. Tycho possessed instruments of excellent quality that could determine the position of stars with the greatest accuracy yet recorded. And to determine precession, he had available the stellar positions from both Ptolemy and the Islamic astronomers which he could compare4.

Given the trend of the constants of precession I’ve just cited trending towards the correct value, Tycho was able to have a sufficient enough handle on the rate of precession that he noticed that the stellar positions given by Ptolemy couldn’t be right: They were all low in ecliptic latitude by approximately $1º$. And in $1598$ in his book Stellarum octavi orbis inerrantium accurata Restitutio5 he suggested a potential reason: Ptolemy copied his star catalog from one created by Hipparchus and adjusted the stellar positions to his own time using the incorrect value for the rate of precession.

Digging into this a bit, Ptolemy states that the time between Hipparchus and him is a period of $265$ years. Using his rate of precession, the stars would have moved $2;39º$. However, using the correct value for the precession, the motion should have been $3;41º$ – off by almost exactly the $1º$ that Ptolemy’s stellar positions were.

In $1797$, Pierre-Simon Laplace published Exposition du System du Monde. In it he suggested that there may be another reason Ptolemy’s stellar positions were incorrect. He proposed that the value of the length of a year that Ptolemy used was slightly too long and that as a result, the position of the mean sun that his model gave during Ptolemy’s own time would be short by $1º$. And since Ptolemy’s methods for determining stellar positions required setting the armillary sphere based on the solar position as calculated from the solar model or the lunar position as calculated from the lunar model which is also dependent on the solar model, this would account for the error.

This was rejected by Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre in the early $19^{th}$ century. He claims that the amount of error is small enough that there simply wasn’t enough time for this error to have accumulated to the degree necessary.

In the late $18^{th}$ century Jerome Lalande suggested that, perhaps Ptolemy wasn’t truly an observational astronomer at all and that all of the “observations” in the Almagest were not so much observations, as values derived from the various models. After all, the Almagest is written as an educational manual to teach concepts and methods. As is the case today, perhaps Ptolemy glossed over the finer details to get his point across. To support this, Lalande points to several points throughout the Almagest where the values Ptolemy cites were not quite right for reality, but would have worked out in such a way that just happened to conform to the theory that Ptolemy was presenting. Indeed, if you recall the post in which we covered Ptolemy’s calculation of the rate of precession from Hipparchus’ observations, Toomer noted several points in which Ptolemy’s calculation of the solar and lunar positions was flawed yet just happened to come out to exactly the value Ptolemy was trying to sell.

Delambre agreed with this position and suggested that the derivation of several parameters makes sense if we see them as trying to reach a conclusion and not being based in true observations. He goes further to suggest that the stars Ptolemy picked to determine his rate of precession were cherry-picked to agree with Hipparchus’ rate of precession.

Ultimately, Delambre does not come to a firm conclusion on whether or not Ptolemy truly did observe and leaves the question open to future historians of science.

Thus far in the discussion, I’ve glossed over a fundamental question: Did Hipparchus even have a star catalog – one that listed the coordinates for the stars in a direct format that Ptolemy could have used as a basis for his own? Or, did the observations Ptolemy cites come from calculations like the ones we’ve seen thus far in the Almagest, which would have required Ptolemy to comb through Hipparchus’ works?

If Hipparchus did have a star catalog, it has been lost to time. However, if it did exist, its absence in the current record is unsurprising since the Almagest was so successful that copyists largely stopped transcribing prior texts. But, if one never existed, then it makes it impossible for Ptolemy to have used it. From the historical record, there is some evidence to suggest Hipparchus did have a catalog as Pliny write that Hipparchus felt the need to create one after witnessing a “new star” so that future astronomers could compare against his catalog although historians question the legitimacy of Pliny’s statement.

In the early $20^{th}$ century, historians of astronomy began uncovering historical texts that, indirectly, shed light on this question. Although they did not find wholesale star catalogs, what they did find was historical texts that had lists of constellations and the number of stars in them. By analyzing the terminology and description of the constellations, researcher clearly linked to the era of Hipparchus thereby establishing that there was at least some sort of survey of stars from Hipparchus. However, Ptolemy’s catalog contained many stars that the inferred Hipparchan catalog did not6. It’s hard to pin down an exact number from such vague sources but Boll attempts to make some inferences and gives the potential number of stars in the Hipparchan catalog to be somewhere between $761$ and $881$. Even at the upper end this is still well short of the number of stars in Ptolemy’s catalog. Thus, this would suggest that Ptolemy couldn’t have copied all of his data from Hipparchus.

The next question that arose was whether or not Ptolemy could have taken the basis of his data from prior astronomers other than Hipparchus. This was something that had been suggested in the $10^{th}$ century by al-Sufi who claimed, without any supporting evidence, that Ptolemy took observations from Menelaus as the basis for his catalog. This possibility was raised again in $1901$ by Bjornbo but is dismissed just as readily for lack of evidence as his sole source is the $16^{th}$ century astronomer Augustinus Ricci who in turn simply cites Al-Sufi7.

The next bit of commentary came from John Dreyer in 1917. In this work he notes that, by and large, stellar positions are given to $\frac{1}{6}$ of a degree or $10$ minutes of arc. This is especially true for the ecliptic longitude for which there are only $4$ exceptions ($3$ of which are in Virgo). However, for ecliptic latitude, there is a distinct group which have their latitude given in $\frac{1}{4}º$ increments (keeping in mind that those stars which have latitudes of a whole number or half a degree could be in either increment). Deyer’s interpretation of this is that these stars were likely observed on a different instrument than the ones which are reported in $\frac{1}{6}º$ increments, potentially by Ptolemy himself. The number of stars that fit this description can account for a large portion of the gap between the potential Hipparchan catalog and that of Ptolemy.

But why, then, do these stars show the same $1º$ bias as all the others? Dreyer cited several potential systematic errors that could account for this including the fact that Ptolemy likely observed the solar position near sunset which can have atmospheric diffraction (of which Ptolemy was completely unaware) of as much as half a degree. The potential of errors in the solar model also arises again here. That Ptolemy used the calculated position of the moon from which to base the position of stars adds an additional layer of potential error.

The combination of these errors, Dreyer concludes, is entirely sufficient to account for the error of all the stars without requiring that Ptolemy have lifted any from Hipparchus, a conclusion Dreyer comes to in a second paper, resurrecting the notion that the primary source of error is one of the sun’s position (from which the position of the stars or moon was measured). If this error is rectified, Dreyer finds that this would have virtually fixed the stellar positions and resulted in a very nearly correct value for the rate of precession of the equinoxes.

This claim was given further evidence shortly thereafter in a 1918 paper by Fotheringham. In this paper, he compared modern methods of the time and location of the equinox to those Ptolemy claimed to have observed8. In these cases, he finds that the error in longitude averages approximately $1º$ low thereby fully explaining the error in Ptolemy’s catalog.

However, the question remained whether Ptolemy had observed all of the stars himself, or if some were still taken from Hipparchus? To answer this question, would require a better understanding of the presumed lost Hipparchan catalog which I’ll explore in the next post.

- This post is almost exclusively taken from Gerd Grasshoff’s History of Ptolemy’s Star Catalog. This text was published in $1990$ and provides a comprehensive history to that point. In this post, I’ll be covering through chapter $3.2$. We’ll continue exploring this history in upcoming posts.

- An understanding of proper motion would be helpful, but isn’t strictly necessary as this has not significantly contributed to the positions of most stars in a significant manner.

- As a reminder, the true value is $1º$ per $72$ years and Ptolemy’s value was $1º$ per century.

- And presumably the observations given by Ptolemy of Hipparchus’, but the sources I’m reading doesn’t state he used these.

- This book was hand written and circulated in manuscript form. It contained positions and magnitudes for $1,004$ stars. It was later published, in an abridged form containing only $777$ of the most accurately determined star positions, in $1602$.

- This is a large discussion in its own right and Grasshoff dedicates several pages to this discussion, digging into things like how it may be related to how Hipparchus drew his constellation borders vs Ptolemy. He also discusses Hipparchus’ Commentary on Aratus which is the only Hipparchan text we have today. In it Hipparchus records that Aratus had a count of stars in each constellation as well, and it was more expansive than the texts from Hipparchus’ time. However, the point remains that Ptolemy included stars that Hipparchus evidently did not even if Hipparchus did comment on then from Aratus.

- Who he refers to as Albuhassin.

- The values he compares are found in this post. He takes the first three values of Ptolemy’s but does not seem to have examined the 140 CE summer solstice.