This is normally the part of the year where it gets difficult to go observing due to extremely cold temperatures at night. However, this week has seen daily highs in the mid 70’s and overnight lows in the mid 50’s. So with clear skies, I knew I needed to get out and observe.

Unfortunately, we’re at roughly a third quarter moon so it rose around 9:30 and was high enough to start being problematic by a little after 10:00. As such, I didn’t feel like making the long drive to Danville and just headed out to Broemmelsiek. The skies there continue to grow more and more light polluted so I was limited to pretty bright stars as it was.

In addition to the brightness limitation, Friday nights the Astronomical Society of Eastern Missouri does their open observing nights out there which helps draw a bit of a crowd. Last night, I frequently stopped to talk to various groups coming by and probably lost at least an hour due to this. Which was fine given I targeted nearly every star bright enough to see anyway.

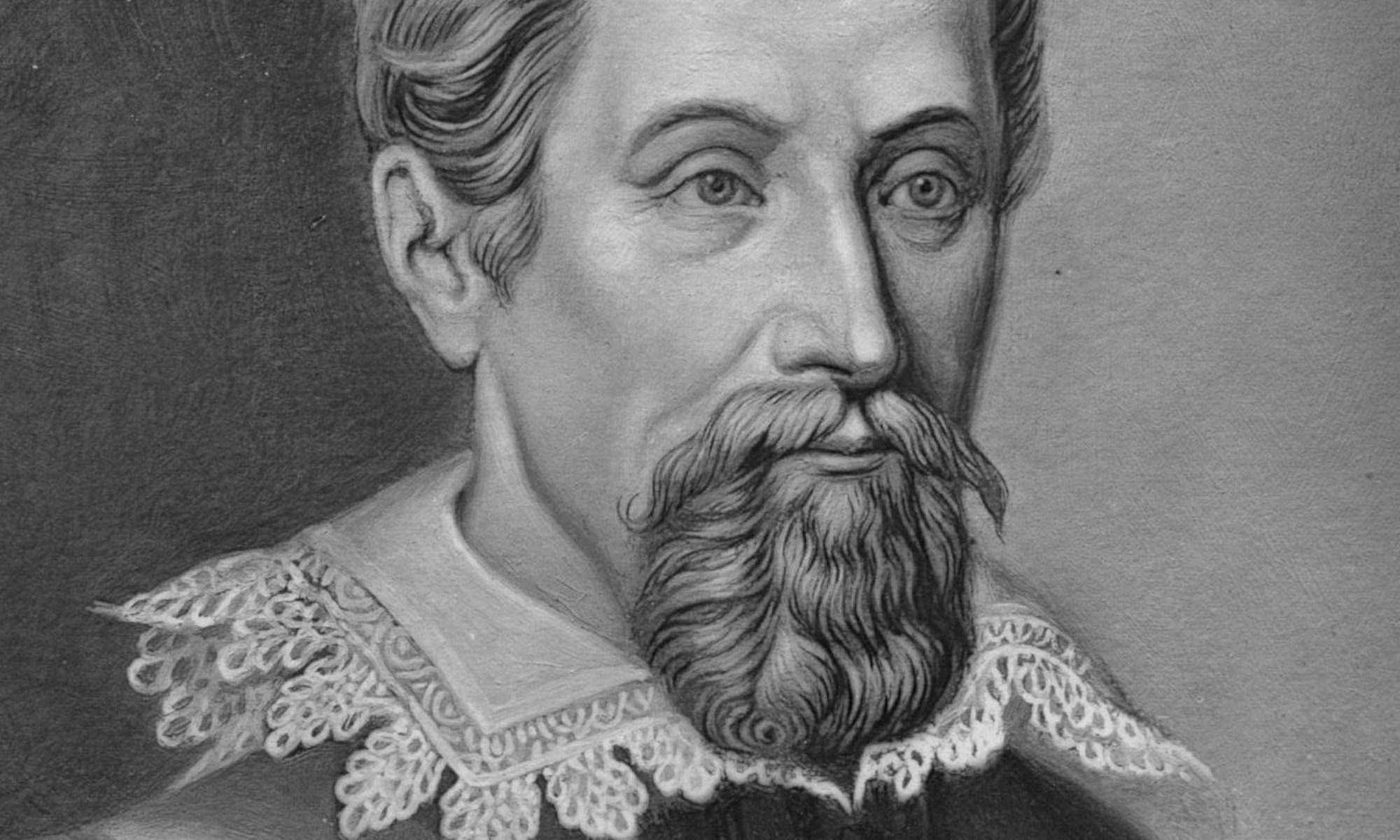

This time, I did do a bit of an experiment. One of my longstanding questions is how the various sights on Brahe’s instrument functioned. In general, we know what they were because of his book, Astronomiae Instauratae Mechanica, but how they actually feel when you use them is a different question. This was something I’d learned rather early on as the current sights on the quadrant are a similar to rifle sights where the idea is to line up the star in the dip of a forward and rearward one.

However, what I immediately discovered was that they end up being impossible to see in the dark making them effectively useless. And any bit of light illuminates them so much that you generally lose being able to see the target for anything fainter than 3rd to 4th magnitude depending on the seeing.

As such, I’ve long wanted to test out other types of sights and last night I made a first attempt at another. This one was based on my solstice and equinox observations of the sun, where I simply tape a long, straight piece of narrow pipe along the sighting edge of the quadrant, and when the light from the sun streams straight through it casting a circular shadow of the pipe, it’s aligned.

This same method should easily be usable for stars but looking down the pipe instead of attempting to find shadows. I figured a piece of $\frac{1}{2}”$ PVC pipe $3$ ft long should give roughly a $\frac{1}{2}º$ of visibility on the far end based on a simple attempt of trying to look down it at the moon, which should get me in the right ballpark.

So I tried this out last night on the first four stars I looked at. Overall, I found it extremely cumbersome to attempt to do as finding the star in such a small window is extremely difficult. Even using the trick often used with a telescope’s finder scope, in which you keep both eyes open, the finderscope has the set of crosshairs to help guide you. Without this, it was virtually impossible to find the star.

As far as how well it worked, that’s a question I haven’t answered yet. My feeling is not particularly well. The data was consistently more than a whole degree off for those limited observations. But to be fair, I also observed the same stars without the pipe and got similar results. All of them had to be tossed out they were so bad. This is something that I find happens quite frequently, where it takes me awhile to really settle into the observing groove and the first several observations are way off. But since I’m not sure if the observations through the pipe were me getting into the groove, or just a poor way to sight objects, I can’t really say if it’s effective or not.

Ultimately, I did get keep 28 observations, 7 of which were new additions to the catalog, all in Auriga. I did the horns of Taurus again which is only the second time I’ve been able to observe this set of stars since, prior to adding the azimuthal ring, it was only a possible target in deep winter, and also hard to target due to how high it gets. So being able to get more observations of these stars is exciting to me.

Orion was starting to rise and visible on the horizon, but by the time the moon really started getting up there, it was still too low on the horizon to want to target as it’s very difficult to observe low altitude objects without an assistant.

As usual, the data is available in a Google sheet.