I first joined the SCA sometime in late 1998 or 1999. At the time, my main interest was just doing the armored combat. While I was active for a few years, college ended up taking me away. GPA before SCA as they say. After trying to do Physics education as a major, then straight Physics, I realized what I most enjoyed were my Astronomy electives and my focus began to shift towards Astrophysics.

Eventually that’s what I majored in but my skills were not sufficient for me to continue past my BS, so after graduating in 2008, I headed into the real world, still with a strong love for the field, but it turns out you can’t do too much with just a BS. So my career took a very different turn.

But one of the advantages of having that adult job was being able to be active in the SCA again. I came back full force in 2015 delving into heraldry, costuming, calligraphy and illumination, brewing, and several other things. And one day, in looking for something entirely unrelated that I can’t recall, I found a picture of an astronomical toolkit from the 16th century. I had no metalworking skills but suddenly, I wanted one. However, before trying to figure out how to make one myself, or commissioning one, I realized I’d need to understand how it worked.

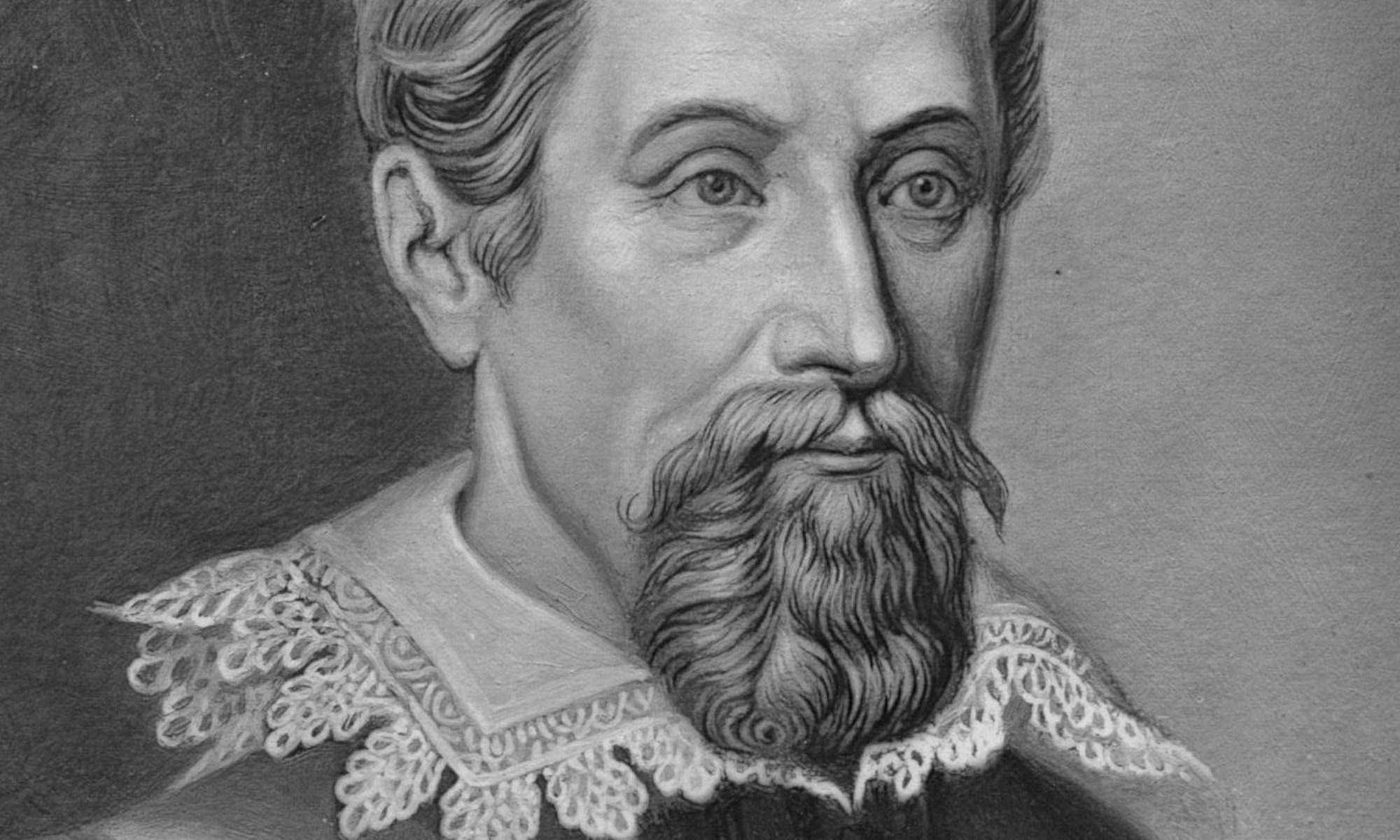

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find much information on the various components, but it got me thinking about medieval astronomy. I knew the cliffs notes version: Greeks came up with a geocentric model with epicycles, Copernicus hypothesized a heliocentric one but couldn’t get it to work because he assumed circular orbits, Kepler figured out they were ellipses, Galileo used a telescope and reinforced Kepler, the Church got involved and it didn’t go well, then Newton gave it a better physical footing with gravity and eventually everyone came around.

But that didn’t really explain much about how everything was figured out. So I started delving more and more into putting together the story of astronomical history, starting from the Greeks, and ending with the publication of Kepler’s Astronomia Nova in 1609. Obviously, Kepler had later works as well, but since they become further and further removed from the period covered in the SCA, I have chosen not to explore them (at least at this time). Similarly, there are numerous other authors who wrote on Astronomy but, by and large, they didn’t contribute anything particularly novel or lasting to the field, so they too will not be explored in any significant depth.

So my overall project has several parts, some of which will be worked on simultaneously:

- To trace and understand all arguments and mathematics in three particular works: Ptolemy’s Almagest, Copernicus’ De Revolutionibus, and Kepler’s Astronomia Nova

- To recreate instruments similar to those that would have been used in period, especially those used by Tycho Brahe on which Kepler based his work

- To use these instruments to measure positions of planets and stars, especially Mars as this was the primary subject of Astronomia Nova

- To use these measurements to:

- Rederive the planetary orbits following Kepler’s mathematics

- Produce a star catalogue in the style of the Uranometria

- Produce a celestial sphere with the stars mapped in a manner similar to Tycho Brahe

- Write a comprehensive summary of the history of astronomy suitable for the layperson, collected with the aforementioned star catalogue, and notes on my methods in recreation, and collect these into a book which will be bound using period methods.

This is understandably a monumental challenge. As I write this, I have begun on the journey and already come to realize that many of the primary sources are terribly difficult to interpret due to the dissimilar frame of mind the writers were in, referencing ideas that have been lost to history as they were often incorrect, and having fundamentally different ways about approaching their mathematics. In addition, the task of recreating the planetary orbits is further complicated in that Kepler was only able to use measurements of Mars when it was at opposition. Given that only happens once every approximately 720 days, this means that accumulating enough data to complete this task will take well in excess of a decade.

And time is of the essence on that count as Mars’ next opposition is on July 27th of this year leaving but 78 days to design and build an instrument.

Fortunately, I can follow much in the footsteps of Kepler with this as well; I need not understand his methods just yet. The measurements come first and making sense of them can come later.